Closer

(2004)

Strangers becoming lovers, lovers becoming estranged: the paradox of oh-so-modern coupling keeps the home fires burning in Patrick Marber's astringent Closer. Marber's play—adapted by the author for Mike Nichols' film—casts a harsh eye on four characters intertwined in a hellish roundelay of fatiguing, obsessive-deceptive relationships. In Nichols' hands, Closer resembles one character's description of a photography exhibition: "It's a bunch of sad strangers photographed beautifully."

Strangers becoming lovers, lovers becoming estranged: the paradox of oh-so-modern coupling keeps the home fires burning in Patrick Marber's astringent Closer. Marber's play—adapted by the author for Mike Nichols' film—casts a harsh eye on four characters intertwined in a hellish roundelay of fatiguing, obsessive-deceptive relationships. In Nichols' hands, Closer resembles one character's description of a photography exhibition: "It's a bunch of sad strangers photographed beautifully."

Marber builds his narrative over big gaps in the lives of two men and two women who forge and destroy romantic relationships in present-day London. Dan (Jude Law), an obituary writer suffering "the Siberia of journalism," memorably meets Alice (Natalie Portman) on the street; strangers who "love" at first sight, they long to get closer, and an accident of fate obliges them.

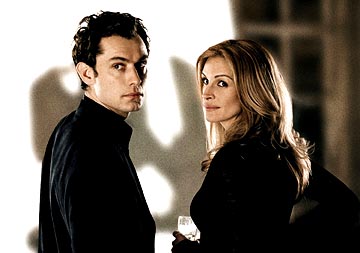

The deceptively charming kick-off—blotted only by the detail that both characters already have a mate—yields to the ravages of time. When next we meet Dan and Alice, they're a long-time couple: she remains a stripper, though he has a published a novel which hardly bothers to veil its dissection of Alice. Their relationship hits the skids when Dan sparks to Anna (Julia Roberts), the professional photographer bound to take his picture, in the film's second of many pas de deux. Alice, sensing trouble, confronts Anna in yet another two-person, pressure-cooking scene. And so it goes.

Further complicating matters is the film's fourth character, a doctor named Larry (Clive Owen) who finds himself, like Dan, embroiled with both women. In an ironic and ruthlessly funny set piece, Dan poses as a woman in an internet chat room and, because he can, invites Larry to meet Anna in a public place. The embarassing prank results in Larry and Anna striking up a relationship, which may or may not have been what the subconsciously self-destructive Dan had deeply in mind all along. All four individuals show their masochistic stripes, as well as their fearful instincts to make their best emotional defense an offense by lashing out at rivals and lovers: after all, who can tell the difference?

Closer suffers from its stylized insularity: the characters aren't realistic, but outsized projections of love's fear and loathing crowded into microscopic dialogues (Law, Portman, Roberts, and Owen have the only speaking roles, aside from a few bit players). Nevertheless, the intimate theatrical simplicity has its advantages. Long ago and far away, Closer would have been an irreverent comic romp; Marber is more austere, drier than his neoclassical forebears, but his quotable deadpan gives good conversation and makes an actor's field day. Most of the talk revolves around deception and, hence, mistrust. Alice remarks, "Lying is the most fun a girl can have with her clothes on, but it's better with them off," while Law refers to lying as "the currency of the world."

All four principals deliver the goods. Law's charm and guile crackle predictably, giving the film much of its much-needed energy. Roberts gives a rare no-nonsense performance, and Portman's unbearable lightness of being glows arduously and ardorously in, emotionally speaking, sickness and in health. As the lone Yanks (Marber and his play are British), Roberts and Portman are strangers in a strange land, adding a yet more alienating otherness to the fractious couples. Owen played Dan on the London stage, and he obviously relishes the opportunity to sink his teeth into the oft-venal Larry, a part he restlessly requested, rather than repetition.

Late in the game, an upper-handed Larry schools Dan: "You don't know the first thing about love because you don't understand compromise." Unlike any of the other characters, Larry is pathologically truthful, but honesty does nothing to mitigate his own possessiveness, jealousy, and inability to trust. The inherent hypocrisy of infidelity—a sin attributed to all four characters—is met with a hypocritical inability to forgive the same. Marber and Nichols sharpen such satirical cynicism to a fine point, but the weapon remains, in the end, decorative. One character's pre-fade-out escape to New York plays as a disingenuous symbol of liberation. Is the impulse to take a vacation from self an admirably self-protective assertion or every bit as devious as a "vacation" from a lover? Perhaps, Marber muses, getting far away is the only genuine triumph. If that's a happy ending, I think I missed it: dark tidings indeed.