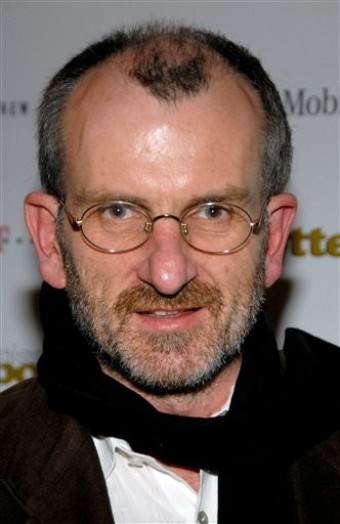

After notable documentary and television work, Chris Noonan made a big splash in Hollywood with Babe, which he directed from a script he co-wrote with George Miller. Over a decade later, he's back in a big way with Miss Potter (about Beatrix Potter, author of the Peter Rabbit books) and a full development slate. I spoke with Noonan at San Francisco's Four Seasons Hotel.

After notable documentary and television work, Chris Noonan made a big splash in Hollywood with Babe, which he directed from a script he co-wrote with George Miller. Over a decade later, he's back in a big way with Miss Potter (about Beatrix Potter, author of the Peter Rabbit books) and a full development slate. I spoke with Noonan at San Francisco's Four Seasons Hotel.

Groucho: What was your own familiarity with The Tales of Beatrix Potter before you signed on to the picture? And then, in working on the project, what have you subsequently seen in them?

Chris Noonan: Right. Well, I didn't read her books as a child, and so I was—I knew of her, of course, and knew who she was. I thought I knew who she was. I thought I knew her story—that she was a woman from long ago who wrote a lot of books for children. And I thought that I knew that all those stories for children were insufferably cute and horribly not to my taste. But I knew nothing about her life.And so, the script—when I first read this first draft of the script that was sent, it really surprised me. I mean, it amazed me. It knocked me out that she had such an incredible story and that I'd never heard it. I think perhaps if she was a male writer, even at that period, we would have heard that story over and over again. And it would have been part of our folklore—you know, there's this writer, and they have this very tragic part of their life, you know? But being who she was and living when she did, we never got to hear it. And I was amazed and was very moved by it. And so it was really just feeling so moved by her story and feeling it was so sort of tragic in its own way that made me think there was a really good film in it.

G: What about when you finally did read her stories? How would you characterize them from your point of view?

CN: Well now, after reading them, I was amazed by her stories as well—when I went to read them—because I find such a wicked sense of humor in them. I found her quite contemporary in a way—those stories quite contemporary. First of all, she presents the world—apart from the fact that her little animal characters wear human clothes and that kind of thing—but she presents the world very much as it is, much more so than other children's writers at that time. You know, it's a world where death happens. It's a world where the fox, who you like, and the duck, who you like, are mortal enemies, and the fox wants to eat the duck. And there's always the presence of mortality in her stories, which I think is really the reason why they've had such longevity in their popularity—that kids, I think, hate to be spoken down to and like the world to be presented as it is. They like to recognize the truth of a story. And she did that in her own way—in her own sort of Victorian way. She presented the world as a tough place that sort of has its highs and lows. And its lows are the death of the duck.

G: Saving Private Ryan was one of the projects you turned down. Why was that not the picture for you?

CN: Because I thought it was corny. The script was corny. And it was also very patriotic and sort of militaristic in a way. And it just wasn't interesting to me. You know, I don't get that patriotism thing. Particularly, being an Australian and putting it into an American context, I don't get that. And particularly, in the sort of modern world, where, let's say America's military adventures don't have my endorsement, you know, I found it alien and not at all inspiring. And good luck to Spielberg for making it work. But he did change the script a great deal.

G: Going back to Miss Potter, in terms of the feminist angle, she seems to have, despite setbacks, ultimately had it all as a woman.

CN: Yeah. Absolutely.

G: And one of the things the film explores is 'to marry or not to marry'—

CN: Yeah.

G: Which ultimately she does. I think audiences might be curious whatever happened to Millie [Ed. Potter's friend, played by Emily Watson].

G: Which ultimately she does. I think audiences might be curious whatever happened to Millie [Ed. Potter's friend, played by Emily Watson].

CN: Indeed.

G: And did she ever marry?

CN: The truth is Millie never did marry. I think audiences will be puzzled about whether Millie was actually a lesbian or whether she was a heterosexual. And I have no idea. And it's impossible to get to the bottom of that. Beatrix and Millie corresponded for the rest of their lives. They were firm friends. And we can only guess. I mean it's very hard to—with the values that we have now—to look back and sort of assign sexual preference to historical figures. It's extremely difficult. Because I think, at that time, women had very passionate relationships with each other. And they'd be horrified to think that people might think it was—there was a sexual ingredient to that. So, yes they were very passionately involved with one another. But I don't really know whether Millie would ever have taken it to another step.

G: You mentioned letters going back and forth there, and I know Potter also kept diaries—coded diaries, right?

CN: Indeed she did.

G: Were those useful at all in—

CN: Absolutely. She not only kept coded diaries; she invented the code the code they were written in, which had to be broken and wasn't broken until something like twenty years ago or so. And it's only recently that all that stuff has been published. However, it seems rather disappointing now because, you know, you think coded diaries from a famous historic figure—there must be something really hot in them. But, in fact, it's sort of—it's very domestic, most of the stuff in those diaries. And I think it was basically to keep her thoughts from her mother that she invented this code and wrote all her diaries in code.

G: That aspect comes out in the film—that privacy from Mom.

CN: Yes, indeed. Indeed. Yeah, her mother and she were not the best of friends for most of her life.

G: I think it was interesting—we were talking earlier about the mortality that's in her books. And in the film, you draw a connection with that animated sequence when she's at her lowest point.

CN: Yes. The animations were very important to me because they give you access to—like an artist expresses their psyche through their work. And I was very anxious to have that work—give that work a reality for the audience and an emotional reality for the audience. And I think it does give you—like, the way I've used it is to give the audience access to her innermost feelings and thoughts at the times of greatest crisis and her greatest highs and lows. Because these are Victorian English times and characters don't walk around sort of going "I'm feeling so depressed," you know? Or "I'm terribly happy today." You know, they don't constantly express themselves like we're encouraged to do today. So it's hard, when you've got a character who won't say what they're feeling, generally. How do you bring the audience with them? So the animations were—one tool that I had to give audiences access to her deepest feelings. And in the initial script, though treated very differently, they were sort of 3-D CGI animations which did come alive on the page, but the animals jumped off the page and came into the room with her, and so she was conversing with sort of three-and-a-half-foot-tall bunnies and frogs and so on throughout the movie, and both Renee and I felt this would sort of, first, make Beatrix look crazy—talking to sort of—

CN: Yes. The animations were very important to me because they give you access to—like an artist expresses their psyche through their work. And I was very anxious to have that work—give that work a reality for the audience and an emotional reality for the audience. And I think it does give you—like, the way I've used it is to give the audience access to her innermost feelings and thoughts at the times of greatest crisis and her greatest highs and lows. Because these are Victorian English times and characters don't walk around sort of going "I'm feeling so depressed," you know? Or "I'm terribly happy today." You know, they don't constantly express themselves like we're encouraged to do today. So it's hard, when you've got a character who won't say what they're feeling, generally. How do you bring the audience with them? So the animations were—one tool that I had to give audiences access to her deepest feelings. And in the initial script, though treated very differently, they were sort of 3-D CGI animations which did come alive on the page, but the animals jumped off the page and came into the room with her, and so she was conversing with sort of three-and-a-half-foot-tall bunnies and frogs and so on throughout the movie, and both Renee and I felt this would sort of, first, make Beatrix look crazy—talking to sort of—

G: Harvey.

CN: Yes, exactly—and secondly, seem like a gimmick and not seem like you were getting closer to her at all but, in fact, it would distance you from her. And thirdly, its problem was that it wouldn't—those creatures wouldn't have felt like they derived from Beatrix's work nearly as much as the way we've treated it in the film now. And I was very lucky to find an animator who could bring that to life in the way she did. She's an amazing woman who grew up in the lake district, who is a devotee of Beatrix's work and is a person trained in all the traditional animation techniques. So she's a cell animator rather than a computer animator. And she just seemed like the perfect person. She's also a sort of weird-looking woman with rings in her eyebrows and lips and so on, and the opposite of what you think of as Beatrix Potter's style. But she had a real sympathetic—a real sympathy, an empathy with Beatrix.

CN: Yes, exactly—and secondly, seem like a gimmick and not seem like you were getting closer to her at all but, in fact, it would distance you from her. And thirdly, its problem was that it wouldn't—those creatures wouldn't have felt like they derived from Beatrix's work nearly as much as the way we've treated it in the film now. And I was very lucky to find an animator who could bring that to life in the way she did. She's an amazing woman who grew up in the lake district, who is a devotee of Beatrix's work and is a person trained in all the traditional animation techniques. So she's a cell animator rather than a computer animator. And she just seemed like the perfect person. She's also a sort of weird-looking woman with rings in her eyebrows and lips and so on, and the opposite of what you think of as Beatrix Potter's style. But she had a real sympathetic—a real sympathy, an empathy with Beatrix.

G: You're invariably described as nice, gentle, soft-spoken, sensitive, genial, professorial, et cetera. Is your personality at odds with the movie biz?

CN: Uhmmmmm.

G: Or would you say "Those don't describe me"?

CN: No, they do describe, at least a large proportion of me. And I think probably most of my cast wouldn't say I was a dictator that sort of tortured them. But, you know, I've found most people I have to deal with in the movie business come around to my way of relating—you know, even Harvey Weinstein, who was involved with this film towards the end, at least: we have a good relationship. It's not that we didn't fight. But he didn't fight dirty with me like I've heard he fights with other people. So, you know, I feel that I've had no experiences in the movie business that convinced me to try and get nastier.

G: Well, that's good. Maybe one way to succeed in Hollywood is to have a lot of balls in the air at the same time. You have a lot of projects in development right now. What is likely to go next for you?

CN: It's very hard to pick, of course. There are two that might happen next. And one of them is a script called Zebras [zeh-bras] or Zebras [zee-bras] in American-speak. Zebras [zeh-bras] in Australian or South Africa-speak, which is set in South Africa in 1973. And it's the story of an under-fifteens soccer team in one of the black townships, which decides it wants to have some white players—wants to be a mixed race team. And so there's a lot of political fallout from that. And so the film covers that political fallout and follows the team's progress over a year. The other one is a project called Third Witch, which is about the youngest of the three witches in Macbeth. And it's a back story and a forward story from the Macbeth plot. And it intersects with the Macbeth plot. And that's an intriguing one as well.

G: What about the Russell Banks project [Ed. Rule of the Bone]? That sounds very intriguing.

CN: Oh yeah. I love that Russell Banks story.

CN: Oh yeah. I love that Russell Banks story.

G: Is that moving forward?

CN: No, it's not.

G: Oh, it's a shame.

CN: No, umm—

G: What happened?

CN: Uhhh, well, Russell and I still love each other, but it went in a direction that he didn't particularly enjoy. At least he felt there was something missing from it. And I was lucky enough to have Russell's generosity in giving me the option to develop that without a fee. So, at that time, I wasn't in any position to sort of pay him anything for that option. And so basically, as it took so long—it took me so long to get to a point where it was filmable—he wasn't prepared to give me any more time, essentially. But he's a wonderful man and I don't resent it at all. And I did sort of—I did wear out my welcome as the recipient of a free option.

[For Groucho's review of Miss Potter, click here.]