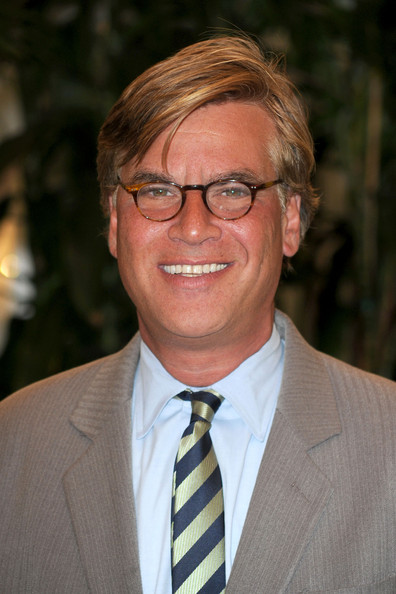

Aaron Sorkin made a major splash in 1989 with the Broadway debut of his play A Few Good Men. Hollywood immediately took notice, hiring Sorkin to adapt his play into a hit film. Sorkin went on to script The American President and Charlie Wilson's War, among others, and to create the television series Sports Night, The West Wing, and Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. He also returned to Broadway in 2007 with his play The Farnsworth Invention, about the creation of television. Sorkin's latest screenplay, for David Fincher's The Social Network, also deals with invention—namely, the creation of the mega-popular social networking website Facebook. Sorkin met the press during a barnstorming college tour that saw him (along with Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, and Armie Hammer) visiting Stanford and U.C. Berkeley; I spoke to him at Berkeley's Claremont Hotel.

Aaron Sorkin made a major splash in 1989 with the Broadway debut of his play A Few Good Men. Hollywood immediately took notice, hiring Sorkin to adapt his play into a hit film. Sorkin went on to script The American President and Charlie Wilson's War, among others, and to create the television series Sports Night, The West Wing, and Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. He also returned to Broadway in 2007 with his play The Farnsworth Invention, about the creation of television. Sorkin's latest screenplay, for David Fincher's The Social Network, also deals with invention—namely, the creation of the mega-popular social networking website Facebook. Sorkin met the press during a barnstorming college tour that saw him (along with Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, and Armie Hammer) visiting Stanford and U.C. Berkeley; I spoke to him at Berkeley's Claremont Hotel.

Aaron Sorkin: I’m Aaron Sorkin. It’s good to meet you.

Groucho: I’m Peter.

AS: Peter…

G: All right.

AS: Go ahead. Beat me up.

(Both laugh.)

G: I’m sure this will probably be put up for, and get, a nomination for adapted screenplay, but I was intrigued to discover that you technically didn’t really adapt the book. You worked in parallel with Ben Mezrich. So can you talk a bit about that process and what you felt was important to research?

AS: Sure. I wouldn’t want to reduce Ben’s role. I don’t think there’d have been a movie if Ben hadn’t come along with a fourteen-page book proposal for The Accidental Billionaires. So that book proposal—his publisher was shopping it around to the studios to get a simultaneous film deal. That’s how it wound up in my hands. And I said—I think I said “yes” on page three, or something. But you’re right. I assumed that the studio would want me to wait until the book was written before I adapted it, that I’d start my work in about a year. They wanted me to start right away, so Ben and I were researching at the same time, writing at the same time. I really, I had no idea what he was going to write. He had no idea what I was going to write. And we met two or three times to share some information and, you know, just tell each other what we knew. I approached it from a slightly different angle, I think, than he did, but like I said, if Ben hadn’t done what Ben did, we wouldn’t be sitting here today.

G: What was most important to you to research as opposed to, you know, using your imagination based on the facts that were already in front of you? AS: Well, there was really two different kinds of research. There was the available research out there that anybody could get their hands on, and then there was the first-person research: talking to the people who are characters in the movie, talking to people who aren’t characters in the movie but were very close to the event and close to the subject. And what became clear was that there were two lawsuits brought against Facebook at roughly the same time, that the defendant, the plaintiffs, and the witnesses came into the deposition room, swore an oath, and what we came away with was three very different versions of a story. And so instead of picking one and deciding, “Well, I think that’s the truth. That’s the story I’ll tell,” or picking one and deciding, “I think that’s the juiciest. That’s the story I’ll tell,” what I liked was that there were three different versions of the story. And that the movie—I would tell all three. I would keep moving from point of view to point of view, whether it’s the Winklevosses or Mark or Eduardo. And have the movie not take a—Rashomon-like—and have the movie not take a position on what the truth was and let those arguments happen in the parking lot. There was nothing in the movie that was invented for the sake of making it sensational. There was nothing in the movie that was Hollywood-ized. There are a couple cases where when it didn’t matter at all, I conflated two characters. There are three cases where I changed a character’s name. One of those characters we never actually see; it’s an off-screen character. In the other two cases it’s just there was no need to embarrass this person more. You have the exact same movie and the exact same truth if you don’t do that. So don’t do that. And that’s it. And then the rest is whatever anybody does when they’re writing nonfiction, you know? If you look at The Queen, Peter Morgan wrote a brilliant script there, but Peter Morgan wasn’t in Queen Elizabeth’s bedroom when she was talking to her husband about their daughter-in-law. You have to be a writer there and write a scene. Speaking of Peter Morgan, same thing with Frost/Nixon. Or William Goldman writing All the President’s Men. He didn’t even know who Deep Throat was, much less what he said. So you imagine those scenes in the garage. We—I, and then we, when David Fincher came along, actually had much more factual information than in any of those movies that I just mentioned. In fact, I’ll give you a very small example. Early in the movie—right, we have a break-up scene with Erica and Mark in a bar, and then Mark goes back to his dorm room and he begins drinking, blogging, hacking, creating Facemash. Facemash goes viral and crashes the Harvard computers. All the while we’re cutting to this punch party at the Phoenix house that’s sort of in Mark’s mind. That’s what’s on the other side of the glass that my nose is pressed up against. And I have Mark’s blog from that night, which we hear almost verbatim in the movie as a voiceover as he’s typing. I say almost verbatim only because I didn’t change anything, I just shortened it a little bit so that it would fit in the space that I needed. And we know that he was drunk because he says in his—he tells us so. He says in his blog, “I’m pretty intoxicated. I won’t lie to you. So what if it’s only ten o’clock.” And so on. And so in writing the scene, the intoxicated part, I had him in the script—he walks into his dorm room, walks into the frame, turns on the computer, walks out of the frame, comes back, the glass goes down, ice goes in the glass, vodka goes in the glass, orange juice goes in the glass, and as begins typing, “Erica Albright is a bitch.” Okay. Shortly before—right before photography started, we found out that it was beer that he was drinking that night. And specifically what kind of beer he was drinking. So David Fincher said, “Okay. We’re not going to do that. He’s going to go to, you know, a little mini fridge in his dorm and he’s going to take out a beer.” I said, “David, come on. It’s—drunk is drunk. That’s the important part. That he was drunk.” The screwdriver is just more cinematic, with the ice cubes going in, and this kind of thing, than just opening up a beer, which isn’t particularly interesting. He said, “I don’t care. If we know that it was beer and we know that it was this kind of beer—” I can’t even remember—like Tecata or—now I can’t remember what kind of beer [Ed. It was Beck’s]. “That’s what it’s going to be.” But two things that you can take away from that story. One: that’s how much we cared about not making stuff up; two: it should tell you something—the fact that we know what kind of beer he was drinking on Tuesday night in October seven years ago should tell you something about how close our research sources were to the subject and the event.

AS: Well, there was really two different kinds of research. There was the available research out there that anybody could get their hands on, and then there was the first-person research: talking to the people who are characters in the movie, talking to people who aren’t characters in the movie but were very close to the event and close to the subject. And what became clear was that there were two lawsuits brought against Facebook at roughly the same time, that the defendant, the plaintiffs, and the witnesses came into the deposition room, swore an oath, and what we came away with was three very different versions of a story. And so instead of picking one and deciding, “Well, I think that’s the truth. That’s the story I’ll tell,” or picking one and deciding, “I think that’s the juiciest. That’s the story I’ll tell,” what I liked was that there were three different versions of the story. And that the movie—I would tell all three. I would keep moving from point of view to point of view, whether it’s the Winklevosses or Mark or Eduardo. And have the movie not take a—Rashomon-like—and have the movie not take a position on what the truth was and let those arguments happen in the parking lot. There was nothing in the movie that was invented for the sake of making it sensational. There was nothing in the movie that was Hollywood-ized. There are a couple cases where when it didn’t matter at all, I conflated two characters. There are three cases where I changed a character’s name. One of those characters we never actually see; it’s an off-screen character. In the other two cases it’s just there was no need to embarrass this person more. You have the exact same movie and the exact same truth if you don’t do that. So don’t do that. And that’s it. And then the rest is whatever anybody does when they’re writing nonfiction, you know? If you look at The Queen, Peter Morgan wrote a brilliant script there, but Peter Morgan wasn’t in Queen Elizabeth’s bedroom when she was talking to her husband about their daughter-in-law. You have to be a writer there and write a scene. Speaking of Peter Morgan, same thing with Frost/Nixon. Or William Goldman writing All the President’s Men. He didn’t even know who Deep Throat was, much less what he said. So you imagine those scenes in the garage. We—I, and then we, when David Fincher came along, actually had much more factual information than in any of those movies that I just mentioned. In fact, I’ll give you a very small example. Early in the movie—right, we have a break-up scene with Erica and Mark in a bar, and then Mark goes back to his dorm room and he begins drinking, blogging, hacking, creating Facemash. Facemash goes viral and crashes the Harvard computers. All the while we’re cutting to this punch party at the Phoenix house that’s sort of in Mark’s mind. That’s what’s on the other side of the glass that my nose is pressed up against. And I have Mark’s blog from that night, which we hear almost verbatim in the movie as a voiceover as he’s typing. I say almost verbatim only because I didn’t change anything, I just shortened it a little bit so that it would fit in the space that I needed. And we know that he was drunk because he says in his—he tells us so. He says in his blog, “I’m pretty intoxicated. I won’t lie to you. So what if it’s only ten o’clock.” And so on. And so in writing the scene, the intoxicated part, I had him in the script—he walks into his dorm room, walks into the frame, turns on the computer, walks out of the frame, comes back, the glass goes down, ice goes in the glass, vodka goes in the glass, orange juice goes in the glass, and as begins typing, “Erica Albright is a bitch.” Okay. Shortly before—right before photography started, we found out that it was beer that he was drinking that night. And specifically what kind of beer he was drinking. So David Fincher said, “Okay. We’re not going to do that. He’s going to go to, you know, a little mini fridge in his dorm and he’s going to take out a beer.” I said, “David, come on. It’s—drunk is drunk. That’s the important part. That he was drunk.” The screwdriver is just more cinematic, with the ice cubes going in, and this kind of thing, than just opening up a beer, which isn’t particularly interesting. He said, “I don’t care. If we know that it was beer and we know that it was this kind of beer—” I can’t even remember—like Tecata or—now I can’t remember what kind of beer [Ed. It was Beck’s]. “That’s what it’s going to be.” But two things that you can take away from that story. One: that’s how much we cared about not making stuff up; two: it should tell you something—the fact that we know what kind of beer he was drinking on Tuesday night in October seven years ago should tell you something about how close our research sources were to the subject and the event.

G: Yeah, yeah…[Yours is] an actor’s perspective, too, isn’t it?

AS: Well, then there’s a whole other thing—

G: Well, your perspective, as an actor.

AS: Yes, I’m also thinking about that, too. But since you raise the subject of actors. It helps that Jesse Eisenberg is playing the part. He is a sensational young actor who never asks the audience to like him. And I have to say that if—Jesse’s about to be a movie star, but he wasn’t when we cast him in this part. And there are a lot of movie stars—frankly there are a lot of directors and a lot of studios—who would have insisted that “Hang on, this character isn’t lovable. Okay, he’s not—we like the cuddly nerds from the eighties, okay? And if this guy isn’t that, at the very least you have to open the movie with a scene of Mark being ten years old and his father beating him brutally with a stick and abusing him so that we’ll forgive him this stuff.” There was never any of that from Jesse, from Fincher, from the studio, anybody. We were just going to own this guy, these guys, and this situation…

G: This [title]’s got that lovely wordplay with Paddy Chayevsky.

AS: Yes, well you just named my hero, but it is—The Social Network is one of those titles that’s meant to mean more to you after the movie than before.

G: You were once accused of writing as if you were perpetually on a first date with a girl you wanted to impress.

AS: Yes.

G: And I thought, you know, with this movie you dramatized that appraisal in that first scene.

AS: That’s exactly right. And it doesn’t work out very well, does it?

(Both laugh.)

G: Well, I was going to ask—you know, it kind of goes back to what I was asking before. I mean, you trained as an actor, and it seems you have to sort of—you need to empathize with all of the characters as you write the script, right? AS: Yeah. You can’t not like the characters that you’re writing...Even with, quote unquote, a “bad guy.” You have to write them as if they’re making their case to God why they belong in heaven. Just as Jack Nicholson does on the witness stand in that big speech. I mean, this is a guy who, clearly this is the villain of the thing, and he makes this speech about how it was probably a good idea that this guy was killed. And we all kind of sit there and go, “I tell you, you got a point.” Um, so the—back in the day when I was studying acting, I think that what—the biggest thing that that helps me do now is I think that even if I write a story that stinks, where the structure just falls apart and nothing works, I think at least I’m writing dialogue that actors could say because I’m playing all the parts while I’m doing it and I’m—

AS: Yeah. You can’t not like the characters that you’re writing...Even with, quote unquote, a “bad guy.” You have to write them as if they’re making their case to God why they belong in heaven. Just as Jack Nicholson does on the witness stand in that big speech. I mean, this is a guy who, clearly this is the villain of the thing, and he makes this speech about how it was probably a good idea that this guy was killed. And we all kind of sit there and go, “I tell you, you got a point.” Um, so the—back in the day when I was studying acting, I think that what—the biggest thing that that helps me do now is I think that even if I write a story that stinks, where the structure just falls apart and nothing works, I think at least I’m writing dialogue that actors could say because I’m playing all the parts while I’m doing it and I’m—

G: You’re giving it that authenticity of voice.

AS: It’s also just that I love the sound of dialogue so much. My parents took me to plays starting from when I was very little. And lots of times they took me to see plays that I was too young to understand like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? when I was eight years old. And so I wouldn’t know—I wouldn’t understand the story that was going on, but I loved the sound of the dialogue. It sounded like music to me. And I really wanted to imitate that sound, of just words crashing into each other, and speeches. It really—it follows the same pattern as the movements of a symphony and I wanted to imitate that sound.