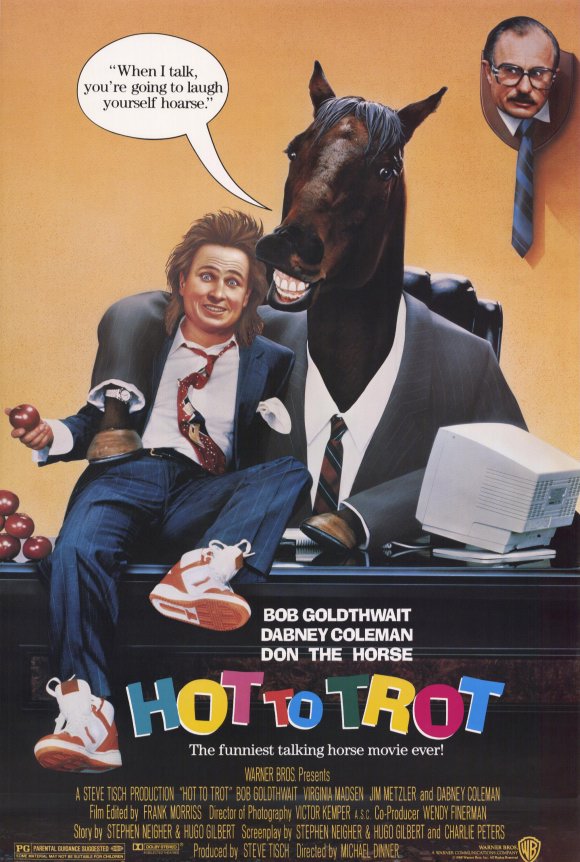

One of the most popular stand-up comics of the '80s, Bobcat Goldthwait is also well-known for his appearances in the Police Academy movies and the notorious flop Hot to Trot, as well as providing the voice of Pain in Hercules. But I like to think of him as the accomplished auteur director of Shakes the Clown (famously called by one critic "the Citizen Kane of alcoholic clown movies") and the Sundance hit Sleeping Dogs Lie. Goldthwait's many, many credits also include roles in Scrooged, Burglar and Blow, and a surprise dramatic turn on CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. He played an absurd version of himself in the Comedy Central original movie Windy City Heat (which he also directed), and he directed Jimmy Kimmel Live between 2004 and 2007. Recently, Bobcat directed his old friend Robin Williams in a new film called World's Greatest Dad. I sat down with Goldthwait in his hotel suite at the Four Seasons in San Francisco, about which the veteran road-tripper was beside himself.

Bobcat Goldthwait: This is—where we are—I’ve gotta be so embarrassing. Yeah, I’m making indie movies, man.

Groucho: You’re used to the dive motels, right?

Bobcat Goldthwait: Sure, man. Well, when I do standup, I’m always in a chain-quality hotel or the worst, which is the "Comedy Condo," which is really just like—it's where most hepatitises start.

Groucho: (Laughs.) Well, my favorite types of comedy movies are farces and, like, legit-screwball type movies and black comedies—all of which are pretty rare it seems. You’ve made a few black comedies. What’s the key to making a good black comedy?

BC: Um, well, I’ll tell you (laughs) when I make these things, I’m not thinking in those terms. But you know what annoys me is lots of times is when a movie doesn’t work, then they call it a black comedy.

G: Ha!

BC: Have you noticed that? Like someone will make a—

G: Like to try to give it more cachet? BC: Yeah. Like "Oh, this is a black comedy." It’s like "No, that’s a big turd, and you’re trying to pretend it"—you know? But I just—I mean, really, this is the kind of stuff that interests me. It’s funny, you said the other things too, farce and screwball, 'cause certainly screwball is something—you know, there’s a couple scenes in this new movie where people are talking fast, and they’re talking over each other and it really made me go "Wow, I really want to make a screwball." There’s a scene when they’re in the teachers' break room. And they all are ganging up on Robin’s character, and it really did make me go "Oh, you know, I’ve always wanted to write a movie about Bigfoot," because I wanted to do a satire on faith, and I didn’t want to set it in the world of churches and stuff—just ‘cause the people who believe in Bigfoot all fight amongst each other really hard. So maybe someday I’ll make "His Girl Bigfoot."

BC: Yeah. Like "Oh, this is a black comedy." It’s like "No, that’s a big turd, and you’re trying to pretend it"—you know? But I just—I mean, really, this is the kind of stuff that interests me. It’s funny, you said the other things too, farce and screwball, 'cause certainly screwball is something—you know, there’s a couple scenes in this new movie where people are talking fast, and they’re talking over each other and it really made me go "Wow, I really want to make a screwball." There’s a scene when they’re in the teachers' break room. And they all are ganging up on Robin’s character, and it really did make me go "Oh, you know, I’ve always wanted to write a movie about Bigfoot," because I wanted to do a satire on faith, and I didn’t want to set it in the world of churches and stuff—just ‘cause the people who believe in Bigfoot all fight amongst each other really hard. So maybe someday I’ll make "His Girl Bigfoot."

G: It’s funny you say that 'cause there’s that scene in the movie where there’s that marquee with His Girl Friday and Freaks, and I thought maybe your next movie should be a hybrid of the two.

BC: Of the two. Well, and I kind of think it is in a weird way, you know?

G: Two divorced freaks rediscover themselves fighting an angry mob.

BC: (Laughs.) Yeah, yeah. And they’re bickering the whole time. That’s a good idea actually. That would be right in my wheelhouse.

G: With the insanity over Michael Jackson, it seems like the time is right for a movie about the way we fetishize tragic death. What is wrong with us?

BC: Yeah. I don’t know why we have to reinvent people. You know, Michael Jackson was a talented singer and a really good dancer. But if one-eighth or one-hundredth of the information that came out about his personal life came out about me, I’d be in jail right now. You know what I mean? If people could digest that—"Sure Bobcat, he’s a creepy dude." But just because he had pet monkeys and merry-go-rounds in his backyard, he’s wholesome? I don’t know, man. So, yeah, that whole rewriting people—I've noticed that older people couldn’t relate to it, and I’m middle aged, but there...[were] some tragic kids in my school, things happened, and everybody changed their ideals of who that person was. And I just went back to my high-school reunion—when I was there, they were doing that. They were lionizing this guy that was a jerk. And my friend Margaret Crennan was like "Yeah, let’s not forget that guy—" and she started heckling. And I was like "Yeah, yeah, yeah," you know. I don’t know why we do that.

G: Well the other thing, from a satirical standpoint, I thought was really interesting in the movie was this idea of whoring out your own pain, or buying somebody else’s pain as entertainment.

BC: Yeah, man. That is what we do. And thanks for pointing that out because I didn’t realize that that’s what I did (laughs), but it is true. It is true. We really do do that. It’s like "Hey—" in our culture now, it’s like "you want to be famous?" "Sure." "Okay, can we film your most embarrassing moments?" "Yeah, no problem." "What?!" I mean, you know, it’s really weird.

G: Yeah. I guess when you’re doing it right, fiction is telling the truth through a lie. Is that sort of what Lance is doing, or is he just an ordinary trouser arsonist?

BC: Uh, no. (Laughs.) I feel that whatever this book is that he wrote in the thing was probably he really was voicing how he did see the world. And for the first time, people did connect. But it wasn’t—you know, it didn’t feel right. So in a weird world, I always feel that maybe Lance was telling his truth, whatever that would be. Yeah.

G: You mentioned one of the funny ideas too is the way you are misremembered after you die or whether you're appropriated. And there’s the gag in the movie about the picture that he hated is the one that everybody is— BC: That comes from me. I know when I die, my obituary photo is going to be me in a police uniform, standing next to a talking horse. I mean, I know that. I know that that’s the clip they’re going to play on Entertainment Tonight. It'll be like "'Bwaaaahaaahaahaa!' Bobcat Goldthwait dies." You know, so, there’s really no way around it, you know?

BC: That comes from me. I know when I die, my obituary photo is going to be me in a police uniform, standing next to a talking horse. I mean, I know that. I know that that’s the clip they’re going to play on Entertainment Tonight. It'll be like "'Bwaaaahaaahaahaa!' Bobcat Goldthwait dies." You know, so, there’s really no way around it, you know?

G: You half-jokingly, I think, told a reporter "Teenagers are idiots, and I don’t want them to go to the movie. I didn’t make it for them, and I think they’re really morons."

BC: Yeah, I do think they’re idiots, and I didn’t make it for them. I’ve gone on to add to that that if you’re really good at Guitar Hero, don’t go to this movie.

G: (Laughs.)

BC: I’m a middle-aged dude. I’m not speaking to them. And of course, you know, I had some kids who come up and they go "Hey, we really liked the movie, and we’re teenagers." And I’m like "Well, that’s ‘cause you’re smart." But also, it could just be a really genius marketing ploy of mine, because I know if you tell teenagers not to do something, then, you know—

G: Right.

BC: If I was a kid, I’d say, "F.U. Bobscratch Goldfarb. I’m going to see your movie."

G: That’s what I was going to say...probably the fifteen-year-old Bobcat would have liked this movie, don’t you think?

BC: Yeah. And here’s what I find really annoying is that when I was a kid I would go to see a Woody Allen movie, right? And he’s talking about Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Now I don’t know what he’s talking about, and that exposed me to Kafka’s Metamorphosis. So R-rated comedies are aimed not at adults, they’re aimed at thirteen-year-olds. And so I really do believe that—even Mel Brooks, who’s obviously very slapstick and very goofy—his movies, in the '70s were aimed at grownups. They weren’t aimed at kids, you know? So that’s—I don’t consider my movies intellectual. I just don’t—you know. You know what’s funny is—and not that I have any amount of success, but now that I’ve made two movies that people perceive as comedies, and I perceive them as comedies, the amount of scripts I get sent to me in Los Angeles (laughs) from studios—and every one’s got a scene where a guy craps his pants. I don’t know what that’s about.

G: There’s your scheisser porn, right?

BC: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I don’t even read 'em. My girlfriend reads a few pages. And then they go across the room into our fireplace. (Laughs.)

G: As a father of two, have you ever received a "World’s Greatest Dad" mug, and if so, did you deserve it?

BC: Hmm. No, I don’t believe I do have a "World’s Greatest Dad" mug. I would like to think I’m like the world’s forty-seventh greatest dad.

G: (Laughs.) That ain't bad!

BC: Like if Alan Thicke dies, and Bill Cosby, I’d just shoot right up.

G: Right. Before you made the film, you said that you wanted to explore family relations. And I wonder if that was the focus that stayed with you all the way through, or if you ended up kind of discovering something else being more of a focus?

BC: Well, what I wanted—really the germ of the idea was to make a movie—and I think this is very unpopular, and it’s even hard for me to say because it’s embarrassing...[about] a male in our society, who actually learns to take care of himself—and it’s really cringe-worthy for me to say. But you know, the idea of loving yourself, not in a masturbatory sense or not in a—

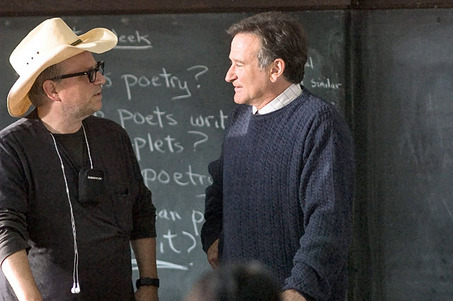

G: New Age way. BC: Not in a New Age way. Because usually people will say, "You gotta spoil yourself." Those people are usually self-obsessed jerks who act incorrectly and under the guise of taking care of themselves 'cause it’s usually a brutish thing to do. But I wanted to make a movie about that, and I didn’t want it to be just a guy with a series of failed female relationships because then it would have just been very misogynistic. So that’s why I said, "Well it’s not just romantic relationships where people turn invisible. You know, there’s also relationships with your kids where you turn invisible and work and all those." So that’s what opened it up to that. I will say this. People always go, "Did you have Robin in mind when you wrote it?" And it’s like if I was going to write a movie for Robin Williams, I wouldn’t have him as a poetry teacher that faces some tragedy. I think he’s already played that pretty well. I think he nailed that pretty good.

BC: Not in a New Age way. Because usually people will say, "You gotta spoil yourself." Those people are usually self-obsessed jerks who act incorrectly and under the guise of taking care of themselves 'cause it’s usually a brutish thing to do. But I wanted to make a movie about that, and I didn’t want it to be just a guy with a series of failed female relationships because then it would have just been very misogynistic. So that’s why I said, "Well it’s not just romantic relationships where people turn invisible. You know, there’s also relationships with your kids where you turn invisible and work and all those." So that’s what opened it up to that. I will say this. People always go, "Did you have Robin in mind when you wrote it?" And it’s like if I was going to write a movie for Robin Williams, I wouldn’t have him as a poetry teacher that faces some tragedy. I think he’s already played that pretty well. I think he nailed that pretty good.

G: Right. Yeah, those scenes do take the piss out of Dead Poets Society with the botched poetry lessons.

BC: You know it’s funny. The cinematographer, Horacio [Marquínez], he—the first day in that classroom, you know, he was standing on the desk (laughs) when Robin came in.

G: Oh, right.

BC: You know, "Oh Captain, my Captain."

G: (Laughs.) The movie is dedicated to your father. Did he help you to develop your sense of humor and your sensibility?

BC: Oh, that’s good, yeah. My dad passed away just as this movie finished. I spent time with him just as soon as I wrapped. Yeah, my old man had this really—he was a sheet metal worker—but a really, really—you know, people talk about how I like—I’m just figuring this out right now—making awkward comedy, be it my early stand-up when I made audiences awkward and these movies I’m making make people awkward. But my old man was really the king of that because he would, like, tell the whole neighborhood that he was going to jump into a jar of mayonnaise from the roof of the 'frigerator. And he would put on a helmet, and he would actually build like a little costume, and we’d talk about it all afternoon, and then the big moment would come, and my dad would climb on top of the 'frigerator. And then there’s always some sort of snafu. And as a little boy, I was always terrified. Not as an adult. But he would do these really elaborate stunts. Like once he built a ramp, and he was going to jump our above-ground pool on a dirt bike. (Laughs.) And there was probably fifty people standing around. And he called it off at the last moment. He built the ramp, and he was actually doing that Evel Knievel thing of pushing the bike up to the lip of it. And, man, I really thought he was going to kill himself. And then the wind was the problem that day. But you know—so, yeah, my dad was like this backyard performance artist who—but all of his pieces were influenced by Budweiser, usually. (Laughs.)

G: (Laughs.) Not sponsored, though, right?

BC: Not sponsored. Yeah, he didn’t have sponsorship, but he was like—so yeah, I think that was when I kind of, like, learned—for me that was kind of how you made people laugh or got their attention.

G: The protagonists of both Sleeping Dogs Lie and World’s Greatest Dad are teachers. And I know you've said in the first case it was sort of a shorthand for altruism—

BC: Yeah.

G: And that would seem to apply here too, in a way, because you could play off the wrongness of a teacher who's caught cheating.

BC: Right. I think it’s just laziness, you know? I started writing another screenplay recently, and I couldn’t believe it that I actually started to contemplate making her a teacher. And I think, "You’re an idiot," you know? So I did not do that. In that screenplay I made her a failed radio producer.

G: Did you have a good experience with teachers or quite the opposite, or both? BC: I had both, you know. I had nuns for all my grammar school, and there I was just told that I was not funny and that I was fat—it was just my first dealings with critics, actually. And I really did. I had like a nun telling me I was fat. It’s no wonder as an adult I had "manorexia" for, like, ten years. And then in high school I still went to a Catholic school but I had these teachers that were kind of very encouraging. You know, Tom Kenny and myself were doing stand-up comedy when we were fifteen. I remember in physics class falling asleep, and the physics teacher going "Well, you know, they did a show last night, and they’re on another journey," and the guy was cool with it, you know? And I had an English teacher that was the same way: Santo Berlotti, who was very encouraging of me writing and stuff. So, yeah. I guess it’s both. I’ve had them be crushing authoritarian figures and then these nurturers.

BC: I had both, you know. I had nuns for all my grammar school, and there I was just told that I was not funny and that I was fat—it was just my first dealings with critics, actually. And I really did. I had like a nun telling me I was fat. It’s no wonder as an adult I had "manorexia" for, like, ten years. And then in high school I still went to a Catholic school but I had these teachers that were kind of very encouraging. You know, Tom Kenny and myself were doing stand-up comedy when we were fifteen. I remember in physics class falling asleep, and the physics teacher going "Well, you know, they did a show last night, and they’re on another journey," and the guy was cool with it, you know? And I had an English teacher that was the same way: Santo Berlotti, who was very encouraging of me writing and stuff. So, yeah. I guess it’s both. I’ve had them be crushing authoritarian figures and then these nurturers.

G: Tell me a little bit about Jack Cheese and Marty Fromage.

BC: Well, all that was is Robin and I would perform sometimes—like, sometimes I would perform as Jack Cheese, and honestly, this is twenty years ago, when me showing up at a club would actually be something you’d have to keep on the downlow. Now, you put my real name there, and there’s still plenty of empty seats. So it's when Robin and I would go out here in the Bay Area and do comedy, and we would just be performing under fake names just because of other concert obligations and stuff. So it was just so we could go out and write, yeah.

G: There’s a running gag in this movie involving Bruce Hornsby. How did you come to choose him, and was he your first choice?

BC: No. My first idea was Michael Bublé, and then I realized that that doesn’t work at all because, you know, I wanted Robin’s character to actually be a fan of the person. I wanted it to be someone who’s valid, you know? And so I made it Bruce, and it was actually Jimmy Kimmel’s brother, Jonathan Kimmel, who suggested him. So I call a friend who produced his albums back in back in the day, and he said—and he just started laughing. It was "Well, I’m working on Bruce’s new album right now." So Bruce came on board, and I’m really excited, because now in hindsight, I look—I go "Well, here’s Bruce." Most of us know him from the 80’s, and they have a pre-conceived notion of him, but people don’t think about Bruce as a jazz musician, he does bluegrass, and the fact that he travels with The Dead and he writes scores for Spike Lee—

G: Yeah.

BC: And it makes me really happy to expose people to him having a sense of humor and exposing some of his music because I—geez, I don’t know what it would be like being a guy from the '80s that people only have one pre-conceived notion of you. (Laughs.)

G: (Laughs.) Right.

BC: So he’s now in the family.

G: Yeah. I got to ask about Shakes the Clown, which, when I was a teenager, I dug that movie. Of course, it was a little—maybe slightly less sophisticated than the ones you’re making now.  BC: Yeah. I watch that movie, and I’m like "What the hell were we thinking?," you know? Tom Kenny and I and Robin and a bunch of us got to see it again recently at the Silent Movie House in Los Angeles, and it was packed, and it was really weird. And I was watching it with my daughter, and she’s like "Dad, you’re a really bad actor," and I’m like, "Yeah, I am!" And I’m not saying that to have a pity party, but I remember now, I wrote it with John Goodman in mind. And I often wonder would it have been any different, you know, ‘cause I don’t know—that’s why I’m not in the movies that I make, 'cause I truly take the stuff really serious, and I want to be able to give it all my focus and concentration. And I have a cameo in this movie, and it was really because I was trying to hire Guillermo from the Jimmy Kimmel show. And he couldn’t get out of work that day. It’s true. And so then I did, like—we scrambled to have a casting session, and we didn’t find anybody, so I just put the suit on and did it. And of course I choked. I walked in and—you know what’s funny? I have no problem—I haven’t discussed this with anyone. I have no problem telling Robin what to do as a director. It’s really true. When I open up the door in that scene, and I was facing him as an actor in the same scene, I just crapped the bed, you know what I mean? It was like—I couldn’t talk. And he goes "Did you forget your lines?" I go "Dude, I just don’t remember the line."

BC: Yeah. I watch that movie, and I’m like "What the hell were we thinking?," you know? Tom Kenny and I and Robin and a bunch of us got to see it again recently at the Silent Movie House in Los Angeles, and it was packed, and it was really weird. And I was watching it with my daughter, and she’s like "Dad, you’re a really bad actor," and I’m like, "Yeah, I am!" And I’m not saying that to have a pity party, but I remember now, I wrote it with John Goodman in mind. And I often wonder would it have been any different, you know, ‘cause I don’t know—that’s why I’m not in the movies that I make, 'cause I truly take the stuff really serious, and I want to be able to give it all my focus and concentration. And I have a cameo in this movie, and it was really because I was trying to hire Guillermo from the Jimmy Kimmel show. And he couldn’t get out of work that day. It’s true. And so then I did, like—we scrambled to have a casting session, and we didn’t find anybody, so I just put the suit on and did it. And of course I choked. I walked in and—you know what’s funny? I have no problem—I haven’t discussed this with anyone. I have no problem telling Robin what to do as a director. It’s really true. When I open up the door in that scene, and I was facing him as an actor in the same scene, I just crapped the bed, you know what I mean? It was like—I couldn’t talk. And he goes "Did you forget your lines?" I go "Dude, I just don’t remember the line."

(Both laugh.)

BG: And so he started laughing, but you know.

G: That’s funny. Have you ever worked with a director as bad as "Bobcat Goldthwait" from Windy City Heat?

BC: (Laughs.) Yeah, you mean somebody who’s encouraging you to do all the worst things? Um, yeah. Yeah. I’ve worked with some—I’ve had some experiences where I’ve worked with —you know, truly I worked with a director that was so bad that’s what influenced me into becoming a director. Like the man had no people skills and such a lack of imagination, I was, like, going "Well, if this idiot can make a movie, I really need to go and give it a shot."

G: Yeah. That makes sense.

BC: That sounds bitter, but it’s really—

G: No, no.

BC: I should give him a special thanks at the—if I ever (laughs)—maybe if I—if I ever win anything, like if I won a [Independent] Spirit Award, maybe I’ll give him a shout out. (Laughs.)

G: Well, it’s true. When you’re faced with incompetence, oftentimes you think, "Why the hell am I not—I could do that. This idiot is—"  BC: Yeah. Yeah. But then there was other directors that were—where the movies I make are not similar in tone at all, but they taught me so much about people skills and things—was like working with Richard Donner. You know, I worked on two things with him, and he really taught me a lot. But what was funny about working with Richard Donner was one day he's like "Kid, you want to direct?" He’s like a big, bigger-than-life character. He was like "Do you want to learn how to direct?" I go "Yeah. Yeah." He goes "Well, come with me in my trailer." I’m like "Wow, Richard Donner’s going to talk to me about directing." And he goes "All right, first thing about directing—take a lot of naps!" (Laughs.) And he throws me a pillow. And we took a nap!

BC: Yeah. Yeah. But then there was other directors that were—where the movies I make are not similar in tone at all, but they taught me so much about people skills and things—was like working with Richard Donner. You know, I worked on two things with him, and he really taught me a lot. But what was funny about working with Richard Donner was one day he's like "Kid, you want to direct?" He’s like a big, bigger-than-life character. He was like "Do you want to learn how to direct?" I go "Yeah. Yeah." He goes "Well, come with me in my trailer." I’m like "Wow, Richard Donner’s going to talk to me about directing." And he goes "All right, first thing about directing—take a lot of naps!" (Laughs.) And he throws me a pillow. And we took a nap!

(Both laugh.)

BG: I fell asleep in his trailer.

G: Oh, man.

BC: It was really weird. I’m like "Uhh, okay."

G: Yeah. He’s quite a character. He has a real reputation for helping people up.

BC: Yeah.

G: But he’s got that, like, old mogul, cigar kind of thing.

BC: But you know what, the thing about Richard Donner—and we’re really digressing here—but he’s such a great man that people don’t even know, like, stuff. Like we were making—I was working on Scrooged, and there was a story in the news where someone had stolen a truck—which I always thought was a pretty good idea for a movie—someone had stolen a truck from a charity organization that fed the homeless. And he didn’t make a thing of it. No one knew about it. I only knew about it 'cause one of his assistants told me—you know, he went out and just bought 'em a truck, you know what I mean? He does that kind of stuff all the time. He’s a really, really sweet man. And when I just saw him recently, I said, you know—I told him about the naps story, and he goes "Well, it’s true!" He didn’t get the—he didn’t think it was funny. He goes "You have to take naps."

G: I’m going to squeeze in one more question here. In the movie, "I Am What I Hate" is Lance’s title for his book.

BC: Right.

G: And that’s something that you've said on more than one occasion.

BC: Oh, sure, yeah, yeah, yeah.  G: You used to satirize stand-up and then you became a stand-up star. And you burned a couch on The Tonight Show, and you ended up being a late-night talk show director for several years.

G: You used to satirize stand-up and then you became a stand-up star. And you burned a couch on The Tonight Show, and you ended up being a late-night talk show director for several years.

BC: Yeah, it’s weird.

G: Is making films kind of the way of avoiding compromise or—it seems like a business that’s designed to push you into compromises: showbiz.

BC: It’s completely designed. If you want to make movies to make money, you’re going to have to compromise. And I really don’t make movies to make money. I truly make movies to make movies. And I feel really weird for all these kids, like, at Sundance who think like "Oh, now I got a movie a Sundance," 'cause, you know, I’ve had two movies. And they don’t realize that’s a destination. That’s not a springboard. It’s really—the fact that you’re going to get to see your movie with people who love movies: that’s the best thing that can ever happen to you if you’re a serious filmmaker. And I’ve already whored out and sold out in so many ways for the past twenty years. I know that—I can tell you—and I'm going to tell you with a straight face, I’m not going to direct "Mall Cop II," you know what I mean?

G: Right, right.

BG: I’m done. If I have to keep renting instead of owning a home, I’ll keep renting. But I know that I’m more fulfilled and happier than I’ve ever been.

G: Well, that’s a great place to stop. Thank you very much.

BC: Thank you, man. Thanks.