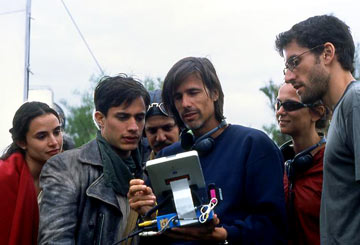

Director Walter Salles (Central Station) steered the major fall release The Motorcycle Diaries, based on Che Guevara's account of his youthful, pre-revolutionary travels (and the corresponding diaries of travel companion Alberto Granado). Recently, Salles sat down with me at San Francisco's Ritz-Carlton Hotel to retrace his tracks.

Groucho:: Your life and career have been greatly influenced by travel. As a diplomat's son, your travels made you somewhat homesick, is that right?

Groucho:: Your life and career have been greatly influenced by travel. As a diplomat's son, your travels made you somewhat homesick, is that right?

Walter Salles: Well, I think that you could say so. So would Freud's neighbor! (Laughs.) The fact is that my option to become a documentarist is a result of this desire to know a little bit better where my roots were. As you said, I—you know, I grew up in different cultures. On the one hand that gave me, you know, the transmitted— the possibility to be permeable to different ways of thinking and to accept diversity, if you want; but on the other hand, I didn't know enough about my own culture, y'know, where I was coming from. And very early on, I decided to do photography and then documentary to be able to dive into the social and political reality of my own country.

G: You also got much of your film education in your youth, starting with a lot of European films, is that right?

WS: Yeah, you know, I lived in Paris for seven years, was very young, I think from five to twelve, maybe. And I hated the climate—the snow in the winter, rain. My father, my parents, travelled constantly. And the only place that I felt really comfortable was in the movie theatre that was almost underneath our house. This is where I was fortunate enough to discover the Italian neo-realists and the whole French Nouvelle Vague, but also the Westerns that were done by John Ford and Howard Hawks or genre films, B-movies, etc. I was exposed to many different forms to narrate, y'know, films very early on, and that was, really, that's cool. I continue to watch at least three or four films a week, y'know, and preferably in the cinema.

G: On reflection, I was really struck by the similarities between Motorcycle Diaries and Central Station, since both are empowering journeys. There's a strong bonding that takes place and then a separation. What do think it is about travel that so profoundly reconstitutes people?

WS: Well, the Tibetans—you know, they say that to travel is to go back to the essence, you know. And I think that they are right because you have to leave a lot of excess baggage behind if you want to unveil a physical and human geography that is unknown to you. I asked the same question to Granado, to Alberto Granado, the man who idealized this journey. I asked him why did he take this journey in the first place, and he said, "Well, because, you know, as a young man who was in his twenties in Argentina, I didn't feel comfortable with the fact that I knew much more about the Greeks or the Romans or the Etruscans than I knew about the Incas. And I wanted to know much more, and I wanted to be transformed by that knowledge," you know? You can travel and not be transformed an iota, y'know? Just take a plane, do fourteen hours, and then end up in a Hilton, y'know, somewhere else. Reminds me of George Bush, George W., who went for the first time to Italy, and, in Rome, he went straight to McDonald's. I think that's very telling, you know? On the other hand, to travel is to be porous to people who think differently from you. It is to get more and more distant from where you come from and closer and closer to who you will be, y'know, you can be. It's about re-baptizing yourself, y'know. And in this sense, I think that you are right: there are links between Central Station and, y'know, Motorcycle Diaries, because they both follow characters who re-baptize themselves through the experience that they have not only on the road but on the margins of the road.

G: You mentioned re-baptizing one's self, and that, to me, is one of the most remarkable scenes in Motorcycle Diaries, which is only a couple of lines in Guevara's book, but it's one of those remarkable occurrences when reality takes on a symbolic significance. How did you see that event, and between you and the screenwriter, Jose Rivera, how did you choose to draw this out?

G: You mentioned re-baptizing one's self, and that, to me, is one of the most remarkable scenes in Motorcycle Diaries, which is only a couple of lines in Guevara's book, but it's one of those remarkable occurrences when reality takes on a symbolic significance. How did you see that event, and between you and the screenwriter, Jose Rivera, how did you choose to draw this out?

WS: Well, first, we were very influenced by Alberto Granado's perception of that moment. You know, Granado, being an eighty-three-years young man, with a remarkable memory. And he redefined a number of the events that were told not only in Ernesto's book, but in his own book, you know, and with the distance that time grants you. Y'know, he told us that "if there was a decisive moment, y'know, in those eight months that we lived together, it was this one. And although it's just a few lines in Ernesto's book and a few paragraphs in my book, I think that this was, by far, the most important moment." So, we did try to grant it, to grant that same importance to the film, and it did have a very emblematic quality. You have a leper colony situated in the Amazon Basin. On one side of the river, you have the doctors and the nuns: that is, the ones who control the power. And on the other hand, you have the—and on the other bank, you had the patients. And on the night of—on his birthday, Ernesto swims to the side you don't expect him to swim to. And therefore opts for the bank of the river in which he would stay for the rest of his life. And there was something very emblematic about that. So in defining early on what the film was about, y'know, we really, how do you say?

G: Honed in?

WS: ...honed in on that, yes. Y'know, I did once a documentary with a Brazilian sculptor, and that man was very smart, much smarter than we all were behind the camera. And he was—but he didn't know how to write nor know how to read. And he carved those immense sculptures out of wood, and these sculptures represented animals that sometimes didn't exist in the Brazilian fauna. And I asked him, "How do you carve giraffes out of that?" And he said, "Oh, that's very easy, you know. I pick up the pieces of wood, and whatever is not a giraffe, y'know, I take out." And in adapting this thing, I was confronted many times with this difficulty in determining what did belong to the narrative and what did not, y'know? And he was sensitive enough to propose an architecture where you can actually see those characters change, but change very delicately throughout the process. So, we didn't want the film to be a politically didactic one, but on the opposite, we wanted this to start as the adventure that it had been for them. And then, the layers of gravity slowly installed themselves.

G: Alberto Granado consulted with you during pre-production, and he also visited the production. Was his presence on location active or passive?

WS: Fundamental. And if you've met Alberto Granado, you would see that the word "passive" makes absolutely no sense in talking about him. Not only did he help us to understand how the leper colony really functioned, but he also helped us to reenact scenes that were very complex. He was the first one to arrive on the set and the last one to leave. And we had a one-hour boat ride going in and out on the Amazon, on very tiny boats with no light at night. And every time I came back with him, he would sing, you know, tangos on the back of that boat. Y'know, we were all exhausted, and he was the only one who was as fresh as an adolescent, y'know?! (Laughs.) So, you learn a lot from a man like that, who, above all, has an extraordinary—one who has, above all, an extraordinary generosity.

G: A high percentage of the film takes place outdoors, so how much did being at the mercy of the elements disrupt the production?

WS: Well, it could have disrupted a lot the production, had we started this film with the concept that we had to receive what nature was granting to us as a gift and not as an adversity. A few examples. We arrived in Patagonia in late spring, early summer. And the moment—the day after we landed in there, there was an extreme snowstorm, and we were caught in the middle of that. And we immediately decided to shoot it, although we were unprepared for a —20 cold. We had no gloves, we were in jeans, but a great part of that crew and also Gael, Gael Garcia Bernal—who's not only a very talented guy but a very courageous one as well—and Rodrigo de la Serna, they opted to just go out there and experience, y'know, that moment, you know? And in doing so, we were being not only faithful to the two books but to the spirit of the books, which was one to go out there in the open and experience what nature and what the people were bringing to you. Y'know, then, in the Amazon, we had temperatures of 105 and 110 degrees Fahrenheit. It was a very physical shoot, but a very emotional one. And we survived, thanks to collective quality that this had.

WS: Well, it could have disrupted a lot the production, had we started this film with the concept that we had to receive what nature was granting to us as a gift and not as an adversity. A few examples. We arrived in Patagonia in late spring, early summer. And the moment—the day after we landed in there, there was an extreme snowstorm, and we were caught in the middle of that. And we immediately decided to shoot it, although we were unprepared for a —20 cold. We had no gloves, we were in jeans, but a great part of that crew and also Gael, Gael Garcia Bernal—who's not only a very talented guy but a very courageous one as well—and Rodrigo de la Serna, they opted to just go out there and experience, y'know, that moment, you know? And in doing so, we were being not only faithful to the two books but to the spirit of the books, which was one to go out there in the open and experience what nature and what the people were bringing to you. Y'know, then, in the Amazon, we had temperatures of 105 and 110 degrees Fahrenheit. It was a very physical shoot, but a very emotional one. And we survived, thanks to collective quality that this had.

G: You had obviously two fine professional actors as your leads and also a great deal of non-professional actors. That must have required a particularly creative approach to integrate those styles of acting, if you will.

WS: Well, you can't blend those two very different forms of representation, y'know, if you're not working with professional actors that are generous, y'know? And Gael and Rodrigo are extraordinarily generous, and they were very sensitive to that and to those encounters that we were making. And also, they blended, y'know, very delicately with the non-actors that we invited to be part of the film. One example. In the leper colony, we worked with five persons who had been patients of the leper colony fifty years earlier. And they were adolescents then; now, they were mens—you know, men in their sixties or seventies. And Gael and Rodrigo never ceased to approach them and to ask them questions and to befriend them. So when the camera arrived, there was something at play already—there was a common history that helped us to find a unity, you know, without homogenizing the narrative. That is the main difficulty is that you don't want to tame everything down. You want, on the other hand, y'know, to heighten the scenes, and at the same time, creating a stream between the actors and non-actors, y'know, in which they can evolve and in which they can improvise and articulate thoughts together. And the role of the director there is—and the role of the camera is almost not to be present, y'know, is to—is one where you would as a spectator have the impression that things are unfolding under your very eyes, and they are not being re-created for you, y'know?

G: You're enormously film-literate. Were you motivated to submerge yourself in your next film Dark Water by the opportunity to explore a new genre?

WS: Yeah, I told you about the experience I had as an adolescent in France, and many of the films I've seen in that period were genre films. But not genre films that were uninteresting. The ones that really struck me were the ones done by Dreyer, for instance, Vampyr by Dreyer—or Nosferatu by Werner Herzog. You know, films that could have been genre films, but that were not because the directors managed to transcend it. So this was something that I wanted to try once, y'know, and to see, y'know, how interesting it could be. And it was, because I worked with very fine actors like, y'know, Jennifer Connelly and John C. Reilly and Tim Roth and Pete Postlethwaite. But I definitely feel, y'know, much closer to Latin American cinema and to the narratives and the stories that we can tell in our own continent. Y'know, there's so much to say over there, and, many times, much more talent than the capacity to express that talent. So I have the certitude that my role is in there and that part of the world.

G: Thank you very much.

WS: Thank you so much.

[For Groucho's review of The Motorcycle Diaries, click here.]